การรุกตรุษญวน

| การรุกตรุษญวน Sự kiện Tết Mậu Thân | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ส่วนหนึ่งของ สงครามเวียดนาม | |||||||

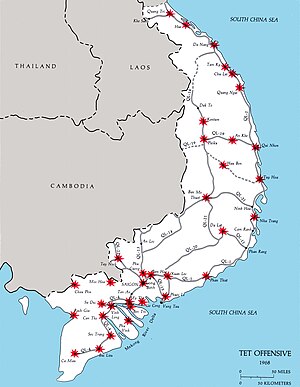

เป้าหมายบางส่วนของคอมมิวนิสต์ระหว่างการรุกตรุษญวน | |||||||

| |||||||

| คู่สงคราม | |||||||

|

กำลังต่อต้านคอมมิวนิสต์: |

| ||||||

| ผู้บังคับบัญชาและผู้นำ | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| กำลัง | |||||||

| ~1,000,000[3] |

ระยะที่ 1: ~80,000 รวม: ~323,000 – 595,000[4] | ||||||

| ความสูญเสีย | |||||||

|

ในระยะที่ 1:

|

ในระยะที่ 1:: กำลังพลสูญเสีย 75,000+ นาย[8] รวมระยะที่ 3: กำลังพลสูญเสีย 111,179 นาย (เสียชีวิต 45,267, บาดเจ็บ 61,267, สูญหาย 5,070)[9] | ||||||

| พลเรือน: เสียชีวิต 14,000 คน, บาดเจ็บ 24,000 คน | |||||||

การรุกตรุษญวน (อังกฤษ: Tet Offensive; เวียดนาม: Sự kiện Tết Mậu Thân 1968, หรือ Tổng tiến công và nổi dậy Tết Mậu Thân) เป็นการทัพทางทหารครั้งใหญ่ที่สุดครั้งหนึ่งในสงครามเวียดนาม เปิดฉากเมื่อวันที่ 30 มกราคม พ.ศ. 2511 โดยกำลังเวียดกงและกองทัพเวียดนามเหนือต่อกำลังเวียดนามใต้ สหรัฐและพันธมิตร เป็นการทัพการโจมตีอย่างจู่โจมต่อกองบัญชาการทหารและพลเรือนและศูนย์ควบคุมทั่วประเทศเวียดนามใต้[10] การรุกนี้ได้ชื่อจากวันหยุดตรุษญวน (เต๊ต, Tết)[11] เมื่อเกิดการโจมตีใหญ่ครั้งแรก

ฝ่ายคอมมิวนิสต์ดำเนินการโจมตีเป็นระลอกในกลางดึกของวันที่ 30 มกราคมในเขตยุทธวิธีเหล่าที่ 1 และที่ 2 ของเวียดนามใต้ การโจมตีช่วงแรกนี้ไม่นำไปสู่มาตรการป้องกันอย่างกว้างขวาง เมื่อปฏิบัติการหลักของคอมมิวนิสต์เริ่มในเช้าวันรุ่งขึ้น การรุกก็ลามไปทั่วประเทศและมีการประสานงานอย่างดี จนสุดท้ายมีกำลังคอมมิวนิสต์กว่า 80,000 นายโจมตีเมืองและนครกว่า 100 แห่ง ซึ่งรวมเมืองหลักของ 36 จาก 44 จังหวัด นครปกครองตนเอง 5 จาก 6 แห่ง เมืองเขต 72 จาก 245 แห่ง และกรุงไซ่ง่อน เมืองหลวงของเวียดนามใต้[12] การรุกนี้เป็นปฏิบัติการทางทหารใหญ่ที่สุดของทั้งสองฝ่ายจนถึงเวลานั้น

การโจมตีขั้นต้นทำให้กองทัพสหรัฐและเวียดนามใต้สับสนและทำให้เสียการควบคุมหลายนครเป็นการชั่วคราว แต่ก็สามารถจัดกลุ่มใหม่เพื่อขับการโจมตีกลับไป ทำให้กำลังคอมมิวนิสต์มีกำลังพลสูญเสียมหาศาล ระหว่างยุทธการที่เว้ การสู้รบอย่างดุเดือดกินเวลาหนึ่งเดือน ทำให้กำลังสหรัฐทำลายนคร ระหว่างการยึดครอง คอมมิวนิสต์ประหารชีวิตประชาชนหลายพันคนในเหตุการณ์การสังหารหมู่ที่เว้ การสู้รบดำเนินไปรอบ ๆ ฐานทัพสหรัฐที่เคซานเป็นเวลาอีกสองเดือน แม้การรุกจะเป็นความพ่ายแพ้ทางทหารสำหรับฝ่ายคอมมิวนิสต์ แต่มีผลลัพธ์ใหญ่หลวงต่อรัฐบาลสหรัฐและทำให้สาธารณชนสหรัฐตะลึง ซึ่งถูกผู้นำทางการเมืองและทหารเชื่อว่าฝ่ายคอมมิวนิสต์กำลังปราชัยและไม่สามารถดำเนินความพยายามมโหฬารเช่นนี้ได้ การสนับสนุนสงครามของสาธารณชนสหรัฐเสื่อมลงและสหรัฐแสวงการเจรจาเพื่อยุติสงคราม

คำว่า "การรุกตรุษญวน" ปกติหมายถึงการรุกในเดือนมกราคม – กุมภาพันธ์ 2511 แต่อาจรวมการรุกที่เรียก "ตรุษญวนเล็ก" ซึ่งเกิดในเดือนพฤษภาคมถึงสิงหาคมด้วย[13]

อ้างอิง

[แก้]- ↑ Smedberg, p. 188

- ↑ "Tet Offensive". History. สืบค้นเมื่อ December 22, 2014.

- ↑ Hoang, p. 8.

- ↑ The South Vietnamese regime estimated communist forces at 323,000, including 130,000 regulars and 160,000 guerrillas. Hoang, p. 10. MACV estimated that strength at 330,000. The CIA and the U.S. State Department concluded that the communist force level lay somewhere between 435,000 and 595,000. Dougan and Weiss, p. 184.

- ↑ Tổng công kích, Tổng nổi dậy Tết mậu thân 1968 (Tet Offensive 1968) – ARVN's Đại Nam publishing in 1969, p. 35

- ↑ Does not include ARVN or U.S. casualties incurred during the "Border Battles"; ARVN killed, wounded, or missing from Phase III; U.S. wounded from Phase III; or U.S. missing during Phases II and III.

- ↑ Steel and Blood: South Vietnamese Armor and the War for Southeast Asia. Naval Institute Press, 2008. P 33

- ↑ Includes casualties incurred during the "Border Battles", Tet Mau Than, and the second and third phases of the offensive. General Tran Van Tra claimed that from January through August 1968 the offensive had cost the communists more than 75.000 dead and wounded. This is probably a low estimate. Tran Van Tra, Tet, in Jayne S. Warner and Luu Doan Huynh, eds., The Vietnam War: Vietnamese and American Perspectives. Armonk NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1993, pgs. 49 & 50.

- ↑ PAVN's Department of warfare, 124th/TGi, document 1.103 (11-2-1969)

- ↑ Ang, p. 351. Two interpretations of the offensive's goals have continued to dominate Western historical debate. The first maintained that the political consequences of the winter-spring offensive were an intended rather than an unintended consequence. This view was supported by William Westmoreland and his friend Jamie Salt in A Soldier Reports, Garden City NY: Doubleday, 1976, p. 322; Harry G. Summers in On Strategy, Novato CA: Presidio Press, 1982, p. 133; Leslie Gelb and Richard Betts, The Irony of Vietnam, Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1979, pp. 333–334; and Schmitz p. 90. This thesis appeared logical in hindsight, but it "fails to account for any realistic North Vietnamese military objectives, the logical prerequisite for an effort to influence American opinion." James J. Wirtz in The Tet Offensive, Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1991, p. 18. The second thesis (which was also supported by the majority of contemporary captured VC documents) was that the goal of the offensive was the immediate toppling of the Saigon government or, at the very least, the destruction of the government apparatus, the installation of a coalition government, or the occupation of large tracts of South Vietnamese territory. Historians supporting this view are Stanley Karnow in Vietnam, New York: Viking, 1983, p. 537; U.S. Grant Sharp in Strategy for Defeat, San Rafael CA: Presidio Press, 1978, p. 214; Patrick McGarvey in Visions of Victory, Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 1969; and Wirtz, p. 60.

- ↑ "U.S. Involvement in the Vietnam War: The Tet Offensive, 1968". United States Department of State. สืบค้นเมื่อ December 29, 2014.

- ↑ Dougan and Weiss, p. 8.

- ↑ "The Myths of Tet". kansaspress.ku.edu. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2021-03-11. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2021-03-08.